Cruising Utilities

The Sunset Blvd Problem

Rosie StocktonOn Adam Miller & Strat Coffman’s Trade Safe Chastity Box

Materials & Applications Storefront, Los Angeles

On view August 7 – November 13, 2025

Cruising up East Sunset Boulevard as it traverses Echo Park and Silver Lake, two of LA’s historically gay neighborhoods, one confronts the pastiche aesthetic of corporate meets DIY securitization strategies characteristic of a city with some of the highest property values and the largest unhoused population in America. The redevelopment along the Boulevard that effectively shuttered historic gay spaces from the 1990s onward has produced the visual effect of clashing class vernaculars: semi-obsolete wrought iron fences painted Dodger blue butt up against the new hygienic powder-coated stainless steel gates. But more prevalent even than the almost nostalgic threat of B&E, is the “theft” of gas, electricity, and water to service the many encampments around East LA that has landlords and city officials concerned now. Where the urban infrastructure protrudes from the grid to service private properties, building owners and tenants implement absurd-looking measures to make sure utilities get where they are supposed to go. Loss prevention is ensured via custom-made and jury-rigged cages covering backflow preventers, AC units, electrical outlets, and water spigots. Locks and chains emerge from holes drilled in the thick plastic of the city’s wastebins to prevent people from salvaging propertied trash. Almost deadpan in their desperation for safety, they read as camp. In an era of total surveillance, when locks, keys, and cages function increasingly as fetish objects, discourses of safety that enabled the redevelopment of Sunset Blvd echo, thirty years later, what Samuel Delany identified in the 1990s as “the Times Square problem.”

Trade Safe Chastity Box installation view, photo by Evan Walsh

In Los Angeles, as in New York, joint appeals to safe sex and safe neighborhoods have long operated as tools of urban redevelopment. It is this precise convergence—the homophobic sexual politics of neoliberal urbanization—that led artists Adam Miller and Strat Coffman, in their recent exhibition Trade Safe Chastity Box, to refigure utility loss prevention cages as chastity boxes. These “chastity boxes” ensure no faithfulness between two beloveds, but a fidelity of the city utilities toward the landlord or designated tenant. While medieval historians have dispelled the myth of chastity belts, reframing them largely as a joke turned curiosity turned kink, the chastity boxes that ensure the utility’s loyalty to the landlord and tenants index the seriousness in every joke. Embroiled in economies of theft and privation, a new erogenous zone is established and secured: where the city hookup (no pun intended) meets the building meter.

Loss Prevention in Public

Miller and Coffman’s Trade Safe Chastity Box, on view this past fall at Material & Application Storefront’s exhibition space, reanimates discourses of security and safety by becoming one such box. Aligning the chastity of sex (locked in by the heterosexual marriage contract) with the chastity of utilities (locked in by the lease), the Trade Safe Chastity Box is at once a monument to the dwindling places for anonymous public sex, a reclamation of the tools of the surveillance state for pleasure, and, theoretically, a place—or rather a stage—to fuck.

“While medieval historians have dispelled the myth of chastity belts, reframing them largely as a joke turned curiosity turned kink, the chastity boxes that ensure the utility’s loyalty to the landlord and tenants index the seriousness in every joke.”

In a city where staving off the fear that the unhoused or displaced might run a rogue electrical cord from an outdoor outlet or strip wires for copper dominates the political imagination, the Box stages the politics of fucking and the politics of social reproduction as inextricable. Inside the gallery, the Box consists of a metal antiseptic room on wheels that takes up the entire space of the gallery. The Box is adorned with various flourishes of property and state surveillance turned sex objects: the loudspeaker, the floodlight, the peephole, the safety mirror, and CCTV cameras. Signifiers of bondage and kink litter the walls and mattresses: a glory hole lined with a rubber glove, rope for binding, two-way peepholes. A lockable stainless-steel rubbish compartment sits next to a spiraled oxidized wrought iron handle, awkwardly bringing eras of metal fabrication and post-industrial modes of production into close proximity. Far outnumbering the locks, chains of keys that could barely secure a childhood diary are strung like bracelets across the walls. Butterfly motifs repeat themselves in the form of superfluous charms and stainless steel structural hinges, a metaphor for delicate forms of life that have mastered the art of disguise, finding safety through flamboyant camouflage, safety in the vulnerability of the public. They turn the loss prevention devices that decorate Sunset Blvd up so loud they become kink.

Trade Safe Chastity Box installation view, photos by Evan Walsh

Staged in what was designed to be the trash sorting room of Warren Techentin Architecture’s more recent (and more noteworthy) development project at 1313 Sunset Blvd, Miller and Coffman’s installation uses materials that echo the aesthetics of the high-end apartment complex, controversially clad in visually cagelike CNC perforated aluminum panels (which, according to the website, provide tenants protection against the harsh sun). Nestled below the flamboyant feat of securitization against (it bears repeating) the sun, lies what Miller and Coffman colloquially refer to as the Box, a room-size architectural device that speaks back to the vernaculars of surveillance, safety, sex, and loss that constitute its very appearance. In the 1970s, Sunset Boulevard had one of the largest concentrations of cruising spots in Los Angeles. Famously, in 1966 the Black Cat Tavern, located near Sunset Junction between Sanborn and Hyperion Avenues, was the site of what some call a pre-Stonewall gay riot, where on New Years Eve undercover cops beat and arrested fourteen queer people for public lewdness and assault on officers. Circus of Books, the 1980s Silver Lake outpost of Book Circus, located a half mile down Sunset, was a well-known refuge for hookups and community meetings during the AIDS crisis. Today, while West Hollywood has the monopoly on mainstream gay clubs, East Sunset still boasts old gay institutions like the beloved Akbar. Elysian Park, sloping up behind 1313 Sunset Blvd, continues to be a long-standing and popular location for anonymous gay sex.

Sex Against Eros

As Miller and Coffman maintain in the exhibition text, in a world where “[d]efensive design structures public experience: Benches with spikes. Empty lots fenced off. Cameras that pierce everywhere,” the Box is here to summon “ghosts of intimacy’s past” and “recontextualize and feature selected archival materials from significant local archives of queer history” in Los Angeles. The exhibition takes on the tone of Sunset Blvd’s particular version of what Samuel Delany would call “rhetorical collisions” that mark the unconscious of class war where not only were working class Latino families driven out of accessing affordable housing, but also decades of gay bars have been forced to slowly close their doors. In this context, where working class domestic life is pushed out and gay sex scatters and finds other public cruising venues like the nearby Elysian Park, the Box seeks—impossibly, In This Economy—to destabilize the divide between private and public space; Miller and Coffman call it a “public boudoir” or “interior streetscape.”

Trade Safe Chastity Box installation view, photo by Evan Walsh

Putting securitization on stage, the metallic symbolics of the cage, lock, and key become an invitation in rather than a means of keeping us out. Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner said as much in the opening provocation of “Sex in Public”: there is nothing more public than privacy. The Box takes the metastasis of loss prevention devices on Sunset Blvd for the project of eros. They are so easily corralled into the erotic, of course, because they are doomed to fail. This is the jouissance of loss prevention: the more one tries to prevent loss, the more visible the impossibility of prevention becomes. Property owners take the side of repetition, trying to hold with cupped hands and caged utilities the city water of enjoyment. For Miller and Coffman, the eroticization of the cages that protect utilities might offer the most literal definition of “safe sex.”

“Putting securitization on stage, the metallic symbolics of the cage, lock, and key become an invitation in rather than a means of keeping us out.”

As the poets and the gays have taught us, eros collapses without its trusty specter of Loss. The erotics of loss and the ways we try to stop it are a well-trodden object of psychoanalysis. Whether you experience loss as pleasure or pain, it doesn’t take a pervert, punk, or militant to have a libidinal investment in seeing chain-link sewn to itself after being trespassed with bolt cutters. Miller and Coffman speak to the particular jouissance of these visible loss prevention measures that dot Sunset Blvd. Sex itself, though, is more complicated than the structure of eros. Departing from Lacan’s jouissance, we might take up psychoanalyst Jean Laplanche’s distinction between sex and eros:

Eros is what seeks to maintain, preserve, and even augment the cohesion and the synthetic tendency of living beings and of psychical life. […] sexuality was in its essence hostile to binding—a principle of “un-binding” or unfettering (Entbindung) which could be bound only through the intervention of the ego—what appears with Eros is the bound and binding form of sexuality.

No euphemism for sexuality, eros is figured as a structure that differentiates the libidinal drives that bind and those that, conversely, unbind, and undo us. Eros is associated with a structural prohibition deferral, whereas sex falls into an unrepresentability, a fantasy of limitless jouissance: the unbound of the Real. In colloquial terms, it is not hard to see that sex “undoes” us. If we lean into the inversion that Miller and Coffman propose: the erotics of the Box secure the possibility of trade’s sex-in-public in contrast to the erotics of the utilities cages securing the passage of utilities-in-private to their tenants. The erotics of the Box offer the possibility of unbinding; the erotics of the utilities cages offer nothing but the normatively bound. We might recall, again, Delany’s intervention into eros here: “Were the porn theaters romantic? Not at all.”

Protecting the utilities’ chaste faithfulness is a way to protect the tenant/owner from the threat of one who might take it away from them, one who is imagined to enjoy beyond the limit of the water bill. There is nothing more libidinally charged—in Lacanian terms, more productive of jouissance—than the specter that someone else might be enjoying at one’s own expense. This is what Lacan calls the “jouissance of the Other”: the fear that elsewhere someone is enjoying more than I and, as Tim Dean put it, “perhaps that whole classes of people are better off than me. Elsewhere jouissance appears unlimited, in contrast to the constrained pleasures that I am permitted to enjoy.” In this regard, any experience of pleasure is intertwined with the Other's jouissance. On the level of the political, this is useful for thinking about mechanisms of social exclusion fueled by the fantasies that those with social or cultural difference, “such as those maintained by other racial and ethnic groups, can provoke the fantasy that these groups of people are enjoying themselves at his or her expense.”[1] The securitization against gay public sex, like the securitization of utilities, is partly a securitization against the fantasy that someone is having fun elsewhere. Harnessing this jouissance and reclaiming privatized pleasure for public good (the enjoyment of surviving?) is one of the provocations that Trade Safe Chastity Box explicitly makes. Queer culture has known this for a long time and, as neoliberal political orders cascade into fascism’s claim on how we ensure the future, questions of sex and property re-encounter one another in the context of the Box.

Trade Safe Chastity Box installation view, photo by Evan Walsh

Inside the Box, a plastic-covered mattress is bound in thick rope tied in shibari knots, where the viewer is invited to do…whatever one wants to do on a mattress: sit, sleep, fuck, scroll, do analysis, re-stage the primal scene? The walls are perforated by rubber diaphragms, flaps, and windows that let the outside in while keeping it out. On one wall, a camera that streams a Twitch stream records the viewers’ movements, and on another a reel of archival footage related to the surveillance and criminalization of gay life in Los Angeles—curated by Cine Apartamento and procured from the ONE Archives—runs on loop. The archival footage is the only nostalgic nod to LA’s history of underground queer culture and gay sex, and lands in the hygienic space more like an irreconcilable open wound than a monument. Aesthetically, we are far from the heyday of the Tom of Finland leather subculture of the 1970s. Instead, the techniques of bondage in the Box refer back to the contemporary police state. The shibari knots operate more like homeless spikes, effectively rendering the mattress—the most literal signifier of the private sphere besides the broom—a publicly denied utility.

“The shibari knots operate more like homeless spikes, effectively rendering the mattress—the most literal signifier of the private sphere besides the broom—a publicly denied utility.”

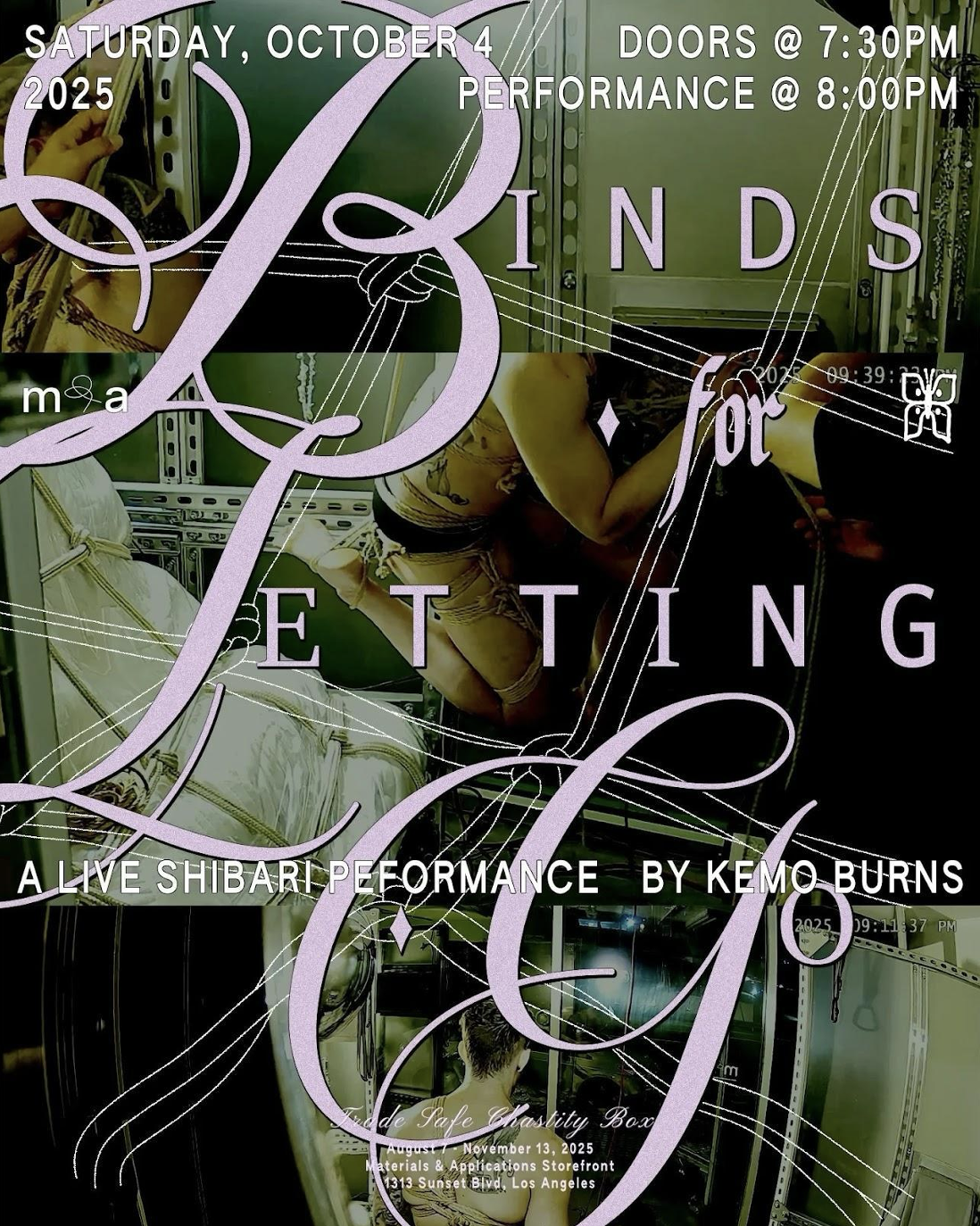

Queers and perverts have always stolen from the grammars of property theft protection to make sex hotter. Bondage gains its power through appropriating the logics of heterosexuality’s need for property logics and cranking them up to the max. As a shibari performance by Kemo Burns called “Binds for Letting Go” held in the Box makes explicit, the erotics of bondage come from binding to our own unfreedom. This loophole—that we might reconfigure constraint as a site to reorient toward freedom—has been elaborated in queer of color critique and Black feminism. What is most evocative in the Box, though, is precisely where erotic symbolization fails to contain jouissance and a traumatic repetition appears, unbound. Despite the Box’s tongue-in-cheek invitation, the iterations of queer fetish objects appropriated from the carceral state to—ironically or genuinely—facilitate a safe space for gay sex as some sort of utopian counterpublic are not what make its intervention meaningful. Rather, a traumatic repetition that pleasure cannot fully redeem is materialized in the bound mattresses—found by the artists on the street—and the archival footage of criminalized gay life that flickers from the wall. Uncomfortable to sit on, the knot-laced mattresses carry whispers of the 1990s “No Cruising” signs that decorated Silver Lake: you still can’t sleep here, you still can’t fuck here. The bound mattress, ironically, returns us to the Laplanchian unbound.

“Binds for Letting Go,” flyer for Kemo Burns’ performance in the Box, flyer by Adam Miller and Strat Coffman

The mattress, we can safely assume, is the site of Freud's “primal scene”: the child’s first encounter with sexuality, marked fundamentally by loss. For Freud, primary trauma emerges due to the subject’s psychic boundaries being breached, a transgression that initiates unforeseen levels of stimulation, excitation, and exclusion that the subjects tries and fails to master with a repetition compulsion. Jean Laplanche takes what Avgi Saketopoulou might call a traumatophilic approach to Freud’s primal scene, introducing the metaphors of binding and unbinding for dealing with “enigmatic signifiers” from the parent. The bound mattress brings us intimately close to Laplanche’s conception of transgenerational trauma, where the child either incorporates the enigmatic signifiers via successful translation and binding, or fails into an “unbound and unbinding intromission”[2] that the ego’s narcissistic structures and meaning-making archives cannot process. These traumatic enigmatic messages function as unruly and unassimilated internal foreign bodies and give rise to an “afterwardsness” that the subject tries to bind into meaning. We might think of the Box as a place to stage this relationship between the unbinding nature of sex and the binding nature of eros, facilitated by the ego. Where the symbol of the bound mattress operates at the limit of sex’s unbinding, erotic fantasies (in the symbolic) compete with traumatic encounters (in the Real) to define the viewer’s encounter with the space.

Safety Unbound

What makes the Box safe? Deployed with a tongue-in-cheek tone, it is worth making clear—as queer theory has done since the ’90s—that for poor people and gays there are no more dangerous political projects than those built in the name of “safety.” Using the redevelopment of Times Square as his case study, Samuel Delany shows how, starting in 1985 after new NYS Public Health Council regulations around the threat of AIDS passed, Midtown Redevelopment Corp had a legal pretense to finally justify closing down places anywhere “high-risk sexual activities” took place: the porn theaters and gay bars along 42nd Street. This law is best known for initiating a wave of bath house closures across the city and for deploying the concept of “safe sex,” New York State managed to criminalize “every individual sex act by name, from masturbation to vaginal intercourse, whether performed with a condom or not.”[3] Peaking in the ’90s, the notion of safety took ideological hold of the political imagination, encapsulating everything from “safe sex” to safe neighborhoods and safe cities to “safe” (e.g. committed or monogamous) relationships and aptly named secure attachments. Delany argues that the safe sexual politics of the 90s society were effectively mobilized to justify the redevelopment of so-called unsafe sexual institutions into condos and offices, and specifically “various institutions that promote interclass communication.” “Safe-sex-shmafe-sex,” Delany writes, “the city wanted to get the current owners out of those movie houses, ‘J/O Clubs,’ […] and peep shows, and open up the sites for developers.”

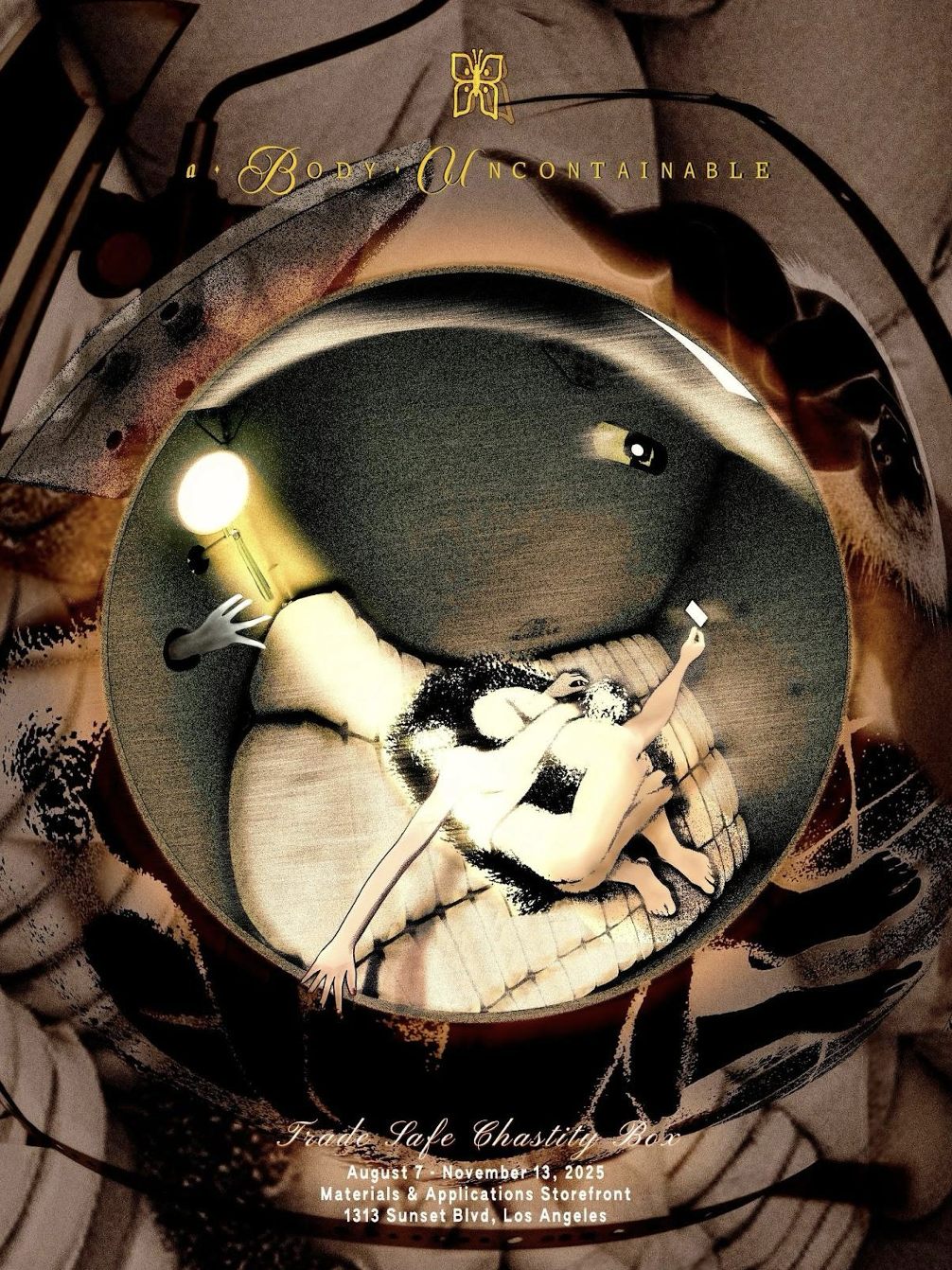

“A Body Uncontainable,” flyer for the opening of the Box, flyer by Adam Miller and Strat Coffman

In this way, Trade Safe Chastity Box emerges alongside iterations of artists and architects working to stage institutional critique at the intersections of sex, city, and criminalization, as manifest in the unofficial “cruising pavilions” that challenged the heteronormative architecture of art spaces at the 16th Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2018, at Ludlow 38 in New York City in early 2019, and at ArkDes, the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design, in late 2019. Restaging historical practices of cruising that were no longer possible due to the urban development of cities, each iteration of Cruising Pavilion interrupted the specific geography of the city to respond to the fact that, as the curators wrote, “geosocial apps have generated a new psychosexual geography spreading across a vast architectonic of digitally interconnected bedrooms, thus disrupting the intersectional idealism that was at play in former versions of cruising.”

Notably, the 2010s marked a reintensification in discourses around the utopian potential of cruising that grew out of the Lee Edelman strand of ’90s queer theory. In response to the racialized and gendered criminalization of safe sex politics, queer negativity offered practices like cruising, barebacking, and chemsex as modes of turning away from the promise of heteronormative reproductive futurism, reclaiming the death drive as a negative structural position to refuse a politics of safety, hope, or progress coherent only via the criminalization of queer people and people of color. In a round table published in 2018, Kay Gabriel argues that cruising “marks out a space of social reproduction,” and, insofar as it happens in public and outside the purview of the nuclear family, it haunts the periphery of propertied love and heterosexual vows. Here, cruising takes on the potential of a utopian form, marking out “a space of social reproduction that, as against the nuclear family, takes place in public; and in superseding the public/private distinction contains the seeds of refusing and overcoming one of the central distinctions that allows for capitalist accumulation, that between production and reproduction.” Of course, there are litanies of criticisms regarding white queer theories’ failure to bring sexual politics into material struggle. Without material politics, without real political struggle, queer negativity ironically calcifies into a “hollow optimism.”

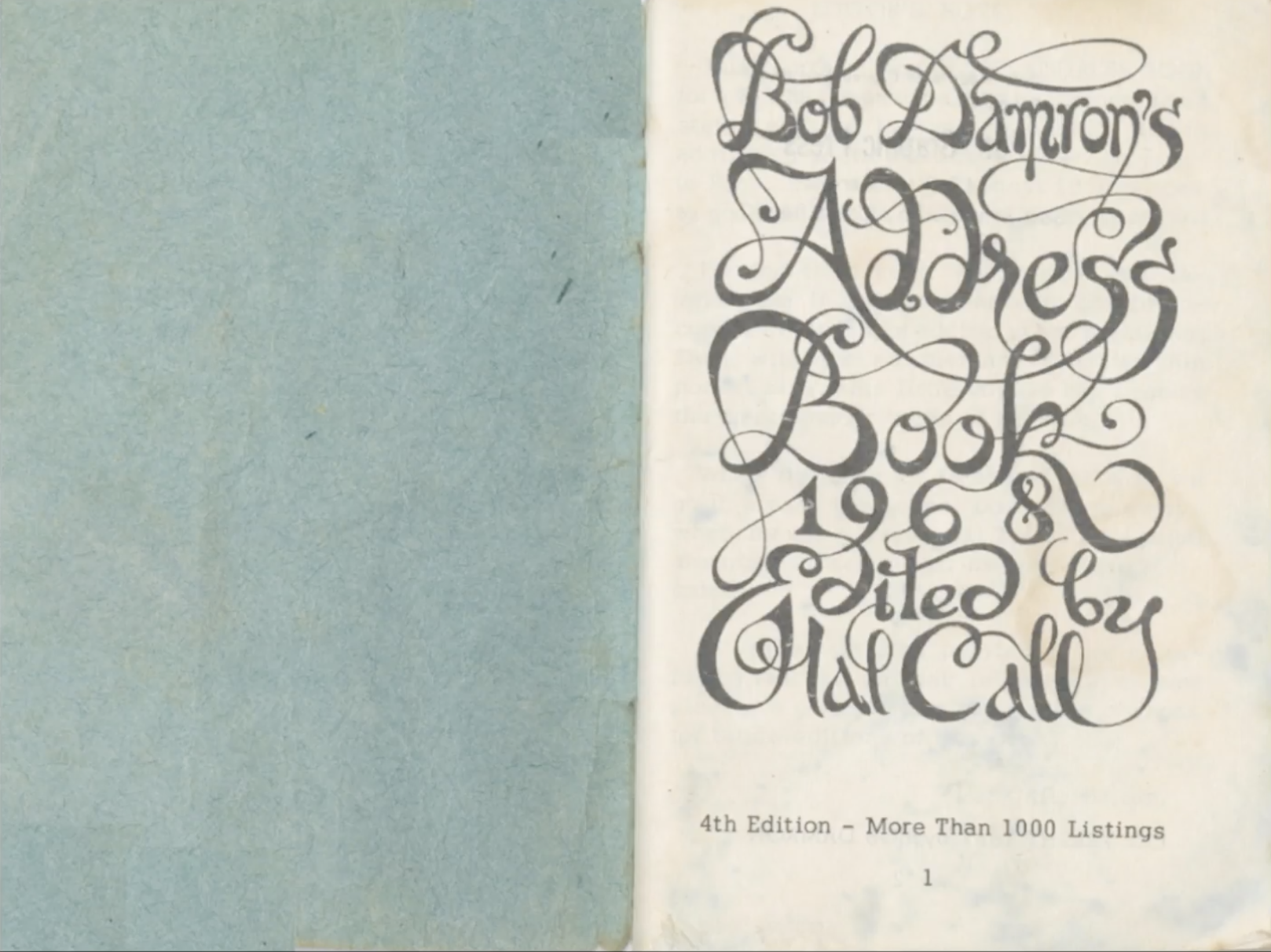

Bob Damron’s Address Book ‘87, archival footage from the ONE Archives, curated by Cine Apartamento

Trade Safe Chastity Box returns, six years after the last Cruising Pavilion, to playfully inquire into the utopian possibilities of cruising in a hyper-surveilled world. What is different now? Affirming the latent possibilities of the counterpublics imagined by 90s cruising utopias, their press release reads:

instead of policing the body, the installation invites the body in—to flicker on a screen, to bump into another pulse. Surveillance devices typically deployed to police our public places—like CCTV cameras, floodlights, peepholes, and safety mirrors—are instead deployed as media for collective hiding and revealing, transforming M&A’s street-facing venue into a performative alleyway that gestures toward the city’s buried histories of cruising, of glances traded in plain view.

The possibility of a utopian impulse in art and architecture remains fraught. We know that queers and artists have always been roped into early stages of gentrification. We get this clearly in Delany’s account of the redevelopment of 42nd Street in Times Square; after the closing of the porn theaters, public art projects decorated the now closed porn theater marquees. In a move to make the neighborhood seem “safer” and more approachable to tourists, New York State Urban Development Corporation’s 42nd Street Development Project collaborated with the nonprofit public art organization Creative Time and the Economic Development Corporation of the City of New York to initiate the 42nd Street Art Project, where site-responsive artworks were exhibited between 7th and 8th Aves in 1993 and 1994.[4] On Sunset Blvd, the Box’s site specificity is critical in this regard, and we might consider the tax break Warren Terechtin Architecture gets from housing a nonprofit gallery, while it buts up against Fernando’s Tires, which has been in operation since 1998.

“As so many have asked, wondered, feared: how will we fuck differently under shifting modes of production and social reproduction, when property relations are abolished? Unfortunately for us, we are far from testing even the most beta mode of the Foucauldian possibility that ‘tomorrow sex will be good again.’”

Free the utilities, Free the trade

The surveilled and locked door of property relations has been appropriated as a symbol of love and social reproduction’s securitization and, like many mechanisms of gratuitous or earned unfreedom, has given itself over to the queers and the perverts, intensified with the apparatus of bondage. Cuffs, ropes, and chastity belts are wrested from their overdetermination as love’s possession and smuggled into the realm of sex’s limits. Could sex be hot against property? As so many have asked, wondered, feared: how will we fuck differently under shifting modes of production and social reproduction, when property relations are abolished? Unfortunately for us, we are far from testing even the most beta mode of the Foucauldian possibility that “tomorrow sex will be good again.” The Box’s accomplishment is in its refusal to capitulate to nostalgia nor a far-off horizon in its quest for a utopian politics of sex and pleasure. It is hard to imagine the possibility that the Box will succeed more in providing cross-class sexual encounters like Delany heralds than in facilitating a developer’s tax break. Rather, the Box doesn’t promise utopia any more than it promises sex.

Perhaps this is point of the Box: not just to provide a stage for fantasizing about cruise trade slipping out of the Elysian and onto the Blvd, but to point out how this fantasy doesn't ensure sex so much as shine a (cop) light back on the cops. It underscores the sexual politics of the tax developers’ break and the sexual nature of the fantasy of utilities theft. Though the exhibition text promises a “pulse” instead of the “police,” the exhibition ultimately stages the impossibility of the vitalist urge to return to the “body” as it is so undeniably haunted and mediated by property relations and flows of wealth. Instead, the Box’s negativity—which is to say, its substantial optimism—isn’t so much in offering a new sexual “counterpublic,” but in its refusal of the neoliberal destitution of (the Other’s) pleasure while opening toward the still unbound traumatic experiences of loss led by developers, cops, armies of voluntary celibates, and monogamists in the project of Making Sex Safe Again.

The Box taunts an optimization of pleasure through unbinding an erotics of loss prevention, where safety is a joke, the closet is on stage, and chastity might be reconfigured as belonging only to the lexical realm of property relations. May we cruise utilities like we cruise trade: in service of freeing modes of social reproduction from the grasp of the surveillance state and its sexual politics of property relations. We may not know if anyone fucked in the Box, but, when I opened the wastebin, I was moved to see people had, in fact, thrown away their trash.

[1] Tim Dean, “Lacan and Queer Theory,” in The Cambridge Companion to Lacan, ed. Jean-Michel Rabaté, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. 250.

[2] John Fletcher, Freud and the Scene of Trauma, New York: Fordham University Press, 2013. 151.

[3] Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red Times Square Blue, New York City: NYU Press, 1999. 120.

[4] Andrew Wasserman, “Times Square Red, White and Blue,” Public Art Dialogue, 2020 Vol. 10, No. 1, 41–63.