The Problem of the Missing Meat

On Bertolt Brecht’s The Mother (a learning play), by the Wooster Group

Adelita Husni Bey“Posted” by Phoebe Greene

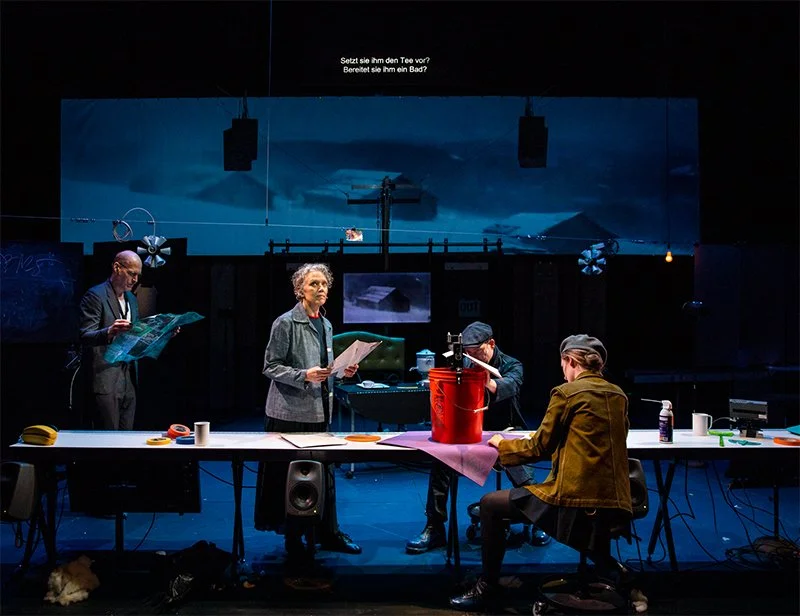

Pelagea Vlasov, Brecht’s titular mother, played by the Wooster Group’s Kate Valk, addresses us from the skeletal remnants of a kitchen. Two rusted burners and a spindly, ripped-up circuit board are resting on a large silver square panel, balanced perilously on a long, thin table that will divide the Wooster Group from the audience for the rest of the play—at once a home and a frontline. In the opening scene of The Mother, Pelagea discusses the soup she’s prepared for her son in perhaps the most quintessential daily mise-en-scène of domestic labor. This lead-in will inaugurate the first stage of the mother’s development in Brecht’s Lehrstücke,[1] her own recognition of her material condition and its as yet incomprehensible cruelty. Yet, because a betterment of her material conditions cannot be won in isolation, Brecht’s mother needs to be orphaned, not only of her son, but of the idea of the family.

In the prologue, Fyodor the teacher (Jim Fletcher), serving as a didactic choir, will reveal and situate the “problem” that binds the mother to the meat, her son, and the revolution:

what can a mother do? ... the problem in the kitchen, the meat that’s missing in the kitchen,

The problem of the missing meat ... won’t be solved in the kitchen.

The tables and the frontline will dance.[2] Nourishment for this worker and her son—how she is fed and will feed—quickly takes center stage. What is the missing meat a stand-in for? The mother’s inner life is thwarted, diminished, obsessively attached to her progeny, her flesh: Pavel, played by Gareth Hobbs, becomes the object of Pelagea’s anxieties, and the familial bond the locus of her sublimation. Poor, hungry and hopeless, she asserts: “I run errands, I do the wash. I turn over every nickel three times. I skimp one time on wood and another time on clothes. But it doesn’t reach. I don’t see any way out.”

This opening scene echoes throughout the play, like a glass bell, clamorous and persistent. Masterfully delivered by Kate Valk, the scene enshrines the tragedy of reproductive work within a society that impoverishes it, leaving its members unable to figure desire beyond the haunting perimeter of the family unit, conveying individuation and paralyzing isolation. Perhaps the opening scene’s missing meat is a proxy for Pavel, with whom the mother ceases to share an intimate world as he moves toward revolutionary immolation. The apparent fraying of the mother-son bond coincides with the gradual creation of relations outside the family unit and the contemporaneous exploration of receiving forms of nourishment. In scene 8, the mother is experimenting with her newfound mask as an agent of the left, distributing leaflets. Meeting the butcher, she recounts being mistaken for a strikebreaker and attacked. The mother, who is constantly tested, must answer whether it is OK to beat strikebreakers; when she replies in the affirmative, the butcher exclaims: “Give her something to eat! Give her two plates!”

At this juncture, ventriloquizing Marx’s “Eighteenth Brumaire,”[3] the mother is described as one of the “hardworking moles. Unknown soldiers of the revolution. Indispensable.” As the play develops, the mother’s growing and insatiable commitment to the revolution will upset her habitual paths of identification. Instead of Fyodor’s “What is a mother to do?,” I find myself observing the mother exceeding her mask, and wonder, how is Pelagea’s concept of mothering breaking its banks? The flesh (of relations) must be made anew.

Earlier in the play, the mother’s woes are interrupted by Pavel’s comrades, Masha (Erin Mullin) and Semjon (Ari Fliakos), who invade the mother’s home with a political task: printing leaflets for the upcoming strike action at the factory. The mother’s fearful reaction is to withdraw further into the kitchen, where she shares with the audience her resistance, expressed as disdain for what she doesn’t yet comprehend: “If I don’t make them tea now, they’ll see right away that I can’t stand them. It doesn’t suit me at all to have them come here and talking so softly I can’t understand anything.” The notion of learning as a radical act (understanding one’s condition) is inexorably linked to class struggle—and it is immediately interrupted by the police. Officers appear onstage only to reinforce the mother’s mask and discipline her reproductive work, exhorting her to “look after her son instead.”

The flesh (of relations) must be made anew.

The Mother was written during the Nazis’ rise to power and premiered on January 17, 1932, at the Komödienhaus am Schiffbauerdamm in Berlin, as Brecht was beginning to develop his theory of the Gestus. The Latin origin of the word suggestively indicates adjectives like “carry,” “bear,” “shoulder,” and translates to “gesture.” It is the word that Brecht chose to represent a certain “attitude”—both detached and evident, caricatured and willful—that actors would need to perform in his political theater. The Gestus is an acting technique that serves to reveal the “real” meaning of the sign—an action that could be interpreted by the audience without much explanation—by hollowing out its perceived plentitude to express its “truth” content. It rests on the idea that a culturally accepted sign is flat, known, semiotically evident, and “full.” Using the representation of fascism as an example, Brecht describes the stiffness of the military march, its “mere pomp,” and states that only when the soldiers are represented as “walking over corpses” can the spectators grasp the Geste, the social gist, of fascism itself. While Aristotelian theater follows a logic of illusion and normative reinforcement—relying on unchallenged and unchanging cultural assumptions—epic theater, which Brecht formulated, is a form of theater wherein the observer is “made to face something,” where “man as a process” is both “alterable and able to alter.” The spectators are alienated rather than compelled to imitate what is happening on stage or find familiar images reassuring. They are encouraged to disidentify. As they engage in this process, viewers are exchanging gazes not solely with the actors—who look back at them—but rather with the play as a whole.

Director Elizabeth LeCompte notes that the piece was made in the spirit of repurposing. Like other Wooster Group works, everything—performers (who typically appear in different roles), ideas, set elements—is recycled, except for an aqua typewriter and a yellow telephone. The Wooster Group translated the play from the German original collectively, with the aid of an interpreter, inserting their own doubts, playful rephrasings, errs and ums, and tweaks to the characters’ original names. Innovating on Brecht’s technique, the voices of the Wooster Group’s actors occasionally arrive from different angles and areas of the stage; these prerecorded voiceovers directly incorporate stage directions from rehearsals as dubbing.

Brecht’s Gestus is doubled by the Wooster Group’s repurposing objects and voices as much as language, generating greater critical distance from the original script. Although the Gestus as a form of delivery sometimes has a pantomimic quality, the nine decades that separate the writing of The Mother from the Wooster Group’s reenactment do not blunt the effect of the play. Valk’s alienating resoluteness, accompanied by recent history itself, convinces me still of the inevitability of uprisings.

In reaching behind the organs of the stage and its capacity to stage, as The Mother does in its engagement with the bones of the act of performing, the play stretches a hand toward psychoanalytic thinking. It is precisely this disidentification, this exchange of looks and recognition with the play itself—its public rehearsal and repetition—that allows the viewer to see the representation as a system of moving parts that can be modeled, critiqued, thought anew; the performative act is not simply taken as evidence, but as possibility. Erwin Piscator, Brecht’s contemporary and friend, wrote about audiences responding physically to political theater performances in the 1930s: invading the stage, dissenting, joining the actors, blurring the line between revolutionary prospect and fiction.[4] The mother’s political consciousness—and perhaps the audience’s, too—is borne of this blur.

The mother’s political consciousness—and perhaps the audience’s, too—is borne of this blur.

Scene 6, focused on the mother’s first attempts at political articulation through language, makes use of the mimetic acts of repetition (learning) and representation (the play itself) through the trope of the classroom, staged, once again, in the kitchen. In the adaptation of a notorious scene, Fyodor the teacher offers to teach the illiterate mother and jobless Gorski—who is, as the character name suggests, unemployed, and only appears in this scene—to read. They sit on the frontline. The teacher stands in front of a blackboard, where he writes the words “branch,” “nest,” and “fish.” “How, for example, do you write worker? For us, branch never comes up,” pleads the mother, encountering the melancholic teacher’s resistance. The workers want to break Fyodor’s tired rehearsal of “education.” They do not want to repeat. They challenge the teacher to reconcile education with political struggle, a form of learning that is in essence processual, dynamic, at odds with the teacher’s cynical, ill-fated parroting.

If we follow Lacan’s pronouncement that “the subject of the unconscious is only in touch with the soul via the body,” then the act of performing is a privileged gateway to the activation of something latent and passive. Theaters may no longer be the harbors of riots as they were from the late eighteenth to the twentieth century, but as The Mother confirms, they may still be spaces to experiment with the spirit of militancy.

The Theater of the Oppressed, a descendant of the Lehrstücke developed by Brazilian director Augusto Boal in the 1970s, relies on the notion of performance as a continual rehearsal, defying the neat confines of a finale. In the practice of Forum Theater, a type of theater with a stated pedagogical function, actors play scenes out over and over while slipping in and out of each other’s roles, amending the script as the repetition unfolds into a different ending. Boal calls participants “spect-actors,” to emphasize their role as observers called to transform a representation by changing the fate of the image[5] through interacting with the company’s actors onstage. The narratives represented in Forum Theater are usually closely linked to the lived reality of the spectators and are often scripted in the preceding weeks through a process that involves developing personal narratives of conflict to ideological ends.

In 2012, I witnessed a woman acting as herself, a housewife in a small Sicilian town, being coaxed into selling her property to a self-styled American landowner who was going to turn the land over to the U.S. navy. Hers was a personal story narrated for a local audience in a small urban amphitheater in southeastern Sicily, not far from Niscemi, a town where local opposition over the U.S. navy’s project of installing a High Frequency Global Communications System node had grown. On that occasion, through the process of Forum Theater led by a local practitioner, spect-actors indignantly rose to their feet, refused the central character’s demise, and volunteered to play the transaction again, ridding themselves of the landowner after many circuitous attempts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these forms of theater also evolved from what Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, terms “conscientization,” a process of developing a critical understanding of social reality through reflection and action. Like the dance between the analysand and the analyst, the repetition must be brought to consciousness, must be witnessed, to upset a character mask. Brecht’s alternative masks, actions, and fates linger through the Gestus, but the fate of the image cannot be changed onstage. Brecht’s revolutionary endings are fixed. Other forms of theater, such as explicitly therapeutic theater, engage a patient in reliving a relational dynamic through and in the presence of others, who aid the patient in becoming witness to their source of perceived suffering. Artist Jo Spence addressed this through her series “Photo Therapy: Transformations” (1984), wherein she played members of her family and used the camera to record herself becoming other, in the tradition of Family Constellations.[6]

Despite (or perhaps because of) a missing father, Pelagea Vlasov’s concept of the family is tightened like a tourniquet around her and her child. Brecht’s foreshortening of the mother’s complexity as a character—stunted, devoid of sexuality, unable to move through pleasure, reliant on the “intermediary of children” for her transformation—remains largely unaltered in the Wooster Group’s production. The mother emerges as “cured” through the gradual manipulation and activation of her unconscious, brought to her circularly via her own flesh: the pain of her son’s loss to the revolution, which she will make her own. On Brecht’s terms, the mother’s road to liberation is a triple liberation: from grief through newfound desire, from the constraints of a limiting notion of motherhood, and from unrecognized class oppression. By the final scene, in the original 1931 script, Pelagea Vlassova (Brecht’s spelling) is restless and unstoppable, constantly exceeding at every role she is offered by her comrades, whose faith is at times shaky. She encourages them:

Those still alive can’t say “never.”

No certainty can be certain

If it cannot stay as it is.

When the rulers have already spoken

That is when the ruled start speaking.

Who dares to talk of “never”?

Whose fault is it if oppression still remains? It’s ours.

Whose job will it be to get rid of it? Just ours.

Whoever’s been beaten must get to his feet.

He who is lost must give battle.

He who is aware where he stands—how can anyone stop him

moving on?

Those who were losers today will be triumphant tomorrow

And from never will come today.

Yet the final scene, appended by the Wooster Group, belies other historical readings. In it, Fyodor the teacher injects the bitterness of multiple defeats and announces, “The war is here,” suggesting that he will buy a condo on Toluca Lake as a final act of resignation. He concludes, from an atemporal position at once within and without America, that “when this whole European journey is over, I think we’ve … we’ve reached the end of the trail.” The mother is unconvinced and demands to continue: “There’s still so much left that I have to do. Where’s my bag?”

At this point Eric Sluyter (sound design and music arrangement) and Irfan Brkovic (video design), who have offered an industrial revolution–themed audiovisual projection, featuring what seems to be the dissolution of flocks of birds into the ether and shooting stars metastasizing into bombs, triumphantly raise a red flag on the screen that sits just above the stage. If the flag feels perhaps anachronistic, its content—the collective fight against impoverishment and exploitation through a recognition of class antagonism—is not. If a flag must be carried, who is going to carry it? Brecht and the Wooster Group both raise this question.

To perceive the repetition of Fyodor’s defeats as final is a failure to understand the shifting historical conditions that must be examined anew. “The cup was full a long time ago, but it needed one drop to make it run over,” exclaims the butcher earlier in the play. History is experienced as a series of repetitions, as a cup that is continuously filled to the brim, only to overflow periodically. Perhaps this is where the play’s faithful restaging can be experienced as pedagogical and not merely didactic, as it may have appeared on the eve of its original premiere, when the play was referencing current events. Today, this reenactment will inevitably incite the audience to draw their own connections to the current historical context, which includes the largest support for labor unions since the 1960s and the most significant uprising in recent U.S. history, in the early summer of 2020. The Mother still agitates.

Although current conditions are far from the revolutionary fervor and possibility that existed in early twentieth-century Russia, where the play is set, The Mother insists that the process of political transformation constantly presents itself as a possibility within the ruins of its previous rehearsal. The function of repetition—of repurposing—so central to the technique of the Wooster Group, serves to express the dichotomous progeny of the revolutionary spirit: Fletcher as Fyodor, who will cease to analyze and be moved in solidarity, and Valk as the mother, who will continue to struggle. For every struggle is both an inevitable continuation and a proclamation of an undying political idea that correctly responds to the present conditions of exploitation.

*

Gathered outside the Performing Garage, after seeing the play in March 2022 Erin Mullin, who played both Masha, the butcher’s wife, and the Bible lady, rejoiced that so many unfamiliar faces were in the crowd. Turning up at the doorstep of this historical bastion of radical theater that has resisted decades of violent gentrification is significant and it feels even more significant now; when, like clockwork, war drums beat halfway around the globe. Amid a European energy crisis that lays bare the contradictions inherent in the privatization of a public good necessary for survival, The Mother reminds us that when nourishment is scarce it will be found through reciting new familial bonds, born out of desire, struggle and necessity. As Brecht wrote, while in exile, in his 1934 poem “The Shopper”:

If all of us who have nothing

No longer turn up where the food is laid out

They may think we don’t need anything

But if we come and are unable to buy

They’ll know how it is.

[1] Brecht’s learning plays were devised as a tool for the working class to learn about communism and as an incitement for the working class to act. They often center a character who has not yet reached political consciousness, a process the audience is in the position to observe and critique.

[2] In describing “the mystical power of objects” and inaugurating the concept of commodity fetishism, Marx—in Capital, vol. 1—chooses the example of a table imbued with the power of movement. I am thinking about the relationships between the “mystical” quality of nascent commodities described by Marx and the Wooster Group’s use of props—tables especially—that reappear, animated by different uses: to cook, to rest on, to address the audience from, as support for printing political flyers, to learn on in scene 6, to demarcate the increasingly blurred line between the kitchen and the street. They are, in this sense, commodities progressively animated toward political ends.

[3] “Europe will leap from its seat and exult: Well burrowed, old mole!” (Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.)” In a wink to Hamlet, Marx suggests revolution inevitably reappears. After a time of burrowing, the mole always pops its head out of a hole.

[4] It should be noted, as the Wooster Group describes on the front page of the libretto, that Brecht and Piscator’s plays, supported by radical unions and working-class theater membership, made for a very different kind of relationship with representation. Erwin Piscator, The Political Theater, (London, Eyre Methuen: 1980), 37.

[5] As a Boal practitioner myself, I often use this phrase to encourage groups I am working with to challenge what they see represented onstage and develop a different political relationship to what they may have previously only perceived as interpersonal conflict.

[6] A therapeutic form of re-enactment, where patients observe narratives of their own generational family conflict and other traumas, which are then played out by other patients.