Atomizing Analysis

The Birth and Death of Community Psychoanalysis in Argentina

Federico PerelmuterOf the roughly 30,000 victims of Argentina’s last military dictatorship, which ruled from 1976 to 1983, around 400, at least, are known to have been mental health workers or students in fields like psychology, social work, education, and psychopedagogy. Most were students. These numbers are inexact by design: these people were disappeared by clandestine “task groups,” never to be seen again, their bodies never found and likely flung out of airplanes into the sea or buried in unmarked graves. Many organizations and institutions around which the field was organized were likewise persecuted and shut down, their leaders terrified into exile or forced to retreat into private clinics. The universities were shuttered or significantly compromised. My analyst, a student of psychology at the University of Buenos Aires at the time, remembered the fear and the hushed words—there were spies hoping to root out “subversives.” Saying the wrong thing to the wrong person could have deadly consequences. Media, the public sphere, and civil organizations mostly collapsed into frightened obedience to a regime whose objective was to eradicate any opposition or critique. Political opposition was effectively outlawed, and unions were brutally targeted. But how and why did therapists, psychologists and analysts become a significant threat to the regime’s project of domination? Why would a right-wing dictatorship that called itself the National Reorganization Process (PRN, by its Spanish initials) disproportionately target the mental health field?

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the world of Argentine psychology and psychiatry was absorbed in a struggle for reform that ran from mental hospitals to reflexology to psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy and community therapy centers in public hospitals. In the 1930s, an institutionalist, hygienist tendency dominated a marginal discipline marked by a lack of effective treatments and the horrifying conditions of mental hospitals. Psychoanalysis was beginning to make inroads among intellectuals and a small subset of adventurous practitioners, privileged enough to have received IPA-certified training in European capitals, founded the Argentine Psychoanalytic Association (APA) in 1942. As psychoanalysis expanded slowly, the APA tightened its regulations, barring those lacking medical degrees and requiring years of costly didactic analysis to become a registered analyst. In parallel, a network of mental health services began to expand in public hospitals, staffed largely by volunteer labor and with a community orientation. Starting in the late 1940s, communist psychiatrists attempted to reconcile psychoanalytic practice and theory with Marxism or dialectical materialism—an endeavor with lasting influence, even if unsuccessful. By the 1960s, with varying degrees of left-wing intensity, the field experienced a boom following the establishment of psychology majors at public universities across the country. Psychoanalysis became a particular fixation of the era’s media, in the throes of that decade’s global political upheavals. By the 1970s, mental health practices were a central preoccupation of Argentine society, from the media to the universities to the public health system.

Yet, as scholars like Marco Ramos and Mariano Plotkin have documented, mental health professionals and institutions constituted both a site of resistance to the dictatorship’s ultraconservative project and a space through which it was put into practice. The PRN’s project was, above all, what Ramos describes as the “blockage of any systematic plan, whether biological, psychoanalytic, or community-based, that would provide its citizens with adequate mental health services.” While the country’s psychoanalytic community has seen itself as driven by a progressivism inherent to psychoanalysis, the degree of attention the mental health field writ large received from the regime demonstrates, more than anything, its centrality to Argentine society and to the pursuit of its improvement. What reemerged, after the dictatorship ended in 1983, was a defanged analytic sphere largely stripped of its community orientation. The reformist movement that had mobilized the field over the previous two decades was extinct, as was much of what could be described as the left.

*

As Mariano Plotkin documents in Freud in the Pampas, the 1940s development of new somatic treatments in psychiatry gave the discipline a new claim to empirical validity, challenging a longstanding eugenic paradigm reliant on preserving social hygiene by sequestering the ill in asylums. In taking distance from medicine to establish its independence, psychiatry became involved in the broader field of mental health, which historian and psychologist Hugo Vezzetti describes as akin to an “applied social science.” Argentine psychoanalysis, meanwhile, had a network of what Plotkin calls “diffusers,” analysts and intellectuals who wrote in women’s and popular magazines for the middle class and framed psychoanalysis in direct relation to that segment. It, too, was beginning to embed itself within mental health disciplines, though for now mostly through the media and intellectual circles, with only a few trained analysts. As a socially embedded field, mental health became open to political contestation, with left psychiatrists in particular seeking to integrate the discipline within a broader materialist worldview, as Vezzetti argues in his book Psiquiatría, psicoanálisis y cultura comunista [Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Communist Culture].

In the USSR, the Zhdanov doctrine, named after party secretary Andrey Zhdanov, was established in 1946 to impugn Western influence, first in literature and eventually in intellectual life, including psychology, and to influence the leadership of global communist parties. Communist psychiatrists in France soon initiated a controversy around psychoanalysis, which they saw as a conservative and bourgeois American perversion upon the minds of the people. Fueled by the spread of the neo-Lamarckian and pseudo-materialist ideas of Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko, party disdain for psychoanalysis intensified around 1949. The party’s intellectual leader, Laurent Casanova, coordinated a broadside titled “Responsibilities of the Communist Intellectual” rejecting the notion of a pure non-political science and theorizing the presence of “two sciences” and “two cultures”—communist and capitalist, Soviet and Western. By 1950, the Soviet academy had begun to promote the reflexological theories of Pavlov as the groundwork for a materialist psychology—unlike the ever-mystifying psychoanalysis—and an “integral science of man,” in Vezzetti’s words. They were influenced by Georges Politzer, a communist philosopher who’d met Freud but renounced psychoanalysis as incompatible with communism before dying while fighting the Nazis. Yet, in France, the communist opposition to psychoanalysis was not long-lived: psychoanalysts quietly left the party in the following years, reformist psychiatrists did not change their ambivalent relationship to psychoanalysis, and the Pavlovian project was largely dead in the water, along with Zhdanovism and Lysenkoism, after Stalin died in 1953. Soon thereafter, Althusser would lead a return to Freud and catapult Lacan into the center of the left-wing French intellectual world of the ’60s.

The Communist Party of Argentina, smaller and more marginal than its French counterpart, had only a handful of psychiatrists, though it was likewise dogmatic: in 1948, for instance, the PCA expelled a group of influential avant-garde artists, the Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención. The most notable communist psychiatrist was Gregorio Bermann, a leader of the 1918 university reform movement that eventually spread throughout Latin America and who had been jailed following a 1930 coup, had served as a medic in the Republican brigades during the Spanish Civil War, and had contributed to the founding of the WHO. Never a party member but a close fellow traveler, in 1949, Bermann echoed the French critique of psychoanalysis in a non-doctrinal communist magazine in Argentina, though the discipline had little influence in the medical community. Peronism, the working-class, fascist-influenced movement led by Juan Domingo Perón, was in power at the time and was regarded by the left as a capitalist cooptation of the working class in part because Peronism’s mass appeal eroded any potential social base for the communist or socialist left. Bermann’s polemic went largely unread, but he founded the Revista Latinoamericana de Psiquiatría [Latin American Psychiatry Magazine] (RLP) in 1951, extending his critique—echoing a French controversy with little applicability in Argentina—until the magazine folded in 1954. Yet a circle of communist psychiatrists formed around the RLP: Jorge Thénon, César Cabral, and José Bleger were the most prominent, though the magazine also featured contributions from around the world.

Bermann, unlike his fellow communists, was never a full party member, and had relationships with many of psychoanalysis’s pioneers. He was particularly close to those more sympathetic to left-wing militancy, such as Marie Langer—a Jewish, Vienna-born-and-trained analyst who’d been exiled to Buenos Aires in the 1930s and went on to cofound the APA—and Enrique Pichon Rivière—a Swiss-born French-Argentine psychiatrist and writer who also co-founded the APA. In 1936, he volunteered in Republican Spain as a psychiatrist in the fight against Franco. In his European travels, Bermann claimed to have met British psychiatrist John Rawlings Rees—who eventually fashioned London’s Tavistock Clinic into a renowned center of socially-oriented psychoanalytic psychotherapy without formal psychoanalytic training—in 1938, when he attended Lacan’s famous March, 1946 lecture, “British Psychiatry and the War.” He would thus come to theorize the notion of “sociopsychiatry,” to affirm “the priority of the material conditions of existence” and distance himself from an asylum-based, social hygienist tradition that he saw as obsolete and politically onerous.

More broadly, Bermann thought that his sociopsychiatry could reconcile what Vezzetti terms “a sociological, critical vision of capitalism inspired by Marxism with a more eclectic disposition concerning issues emerging from post-war social psychiatry.” Though he was familiar with English and American innovations, he vocally disavowed them and followed the communist party line. Yet Bermann’s “eclectic disposition” ultimately failed to influence the field as a whole, as did the RLP, because it couldn’t fit within its broader shift toward “communicating psychiatry with psychoanalysis and the social sciences,” as Vezzetti has it. Following travel to China and the events of the Cuban revolution in 1959, Bermann distanced himself from the Communist Party and moved towards a more solidly medical vision, even as Pichon-Rivière distanced himself from the APA and began developing a model of a non-medicalized social psychology.

Yet, as Vezzetti shows, Bermann’s RLP proved influential. José Bleger was a communist neurologist and writer for RLP, as well as a mentee of first Bermann and Pichon-Rivière, his training analyst. He published the tome Psicoanálisis y dialéctica materialista [Psychoanalysis and Materialist Dialectics] in 1958. The book, a detailed exegesis of Georges Politzer’s oeuvre, was an attempt to break down the communist party lines by aligning psychoanalysis with dialectical materialism through an interrogation of Freudian epistemology. Outrage soon followed, first among psychiatrists but, with the publication of a review in the PCA’s most prominent intellectual outlet at the time, Cuadernos de Cultura, the Bleger case became a broader subject of party outcry. He was going against an orthodoxy that was, itself, mostly dying. The Party’s intellectual committee held a hearing and Bleger was cast out officially in 1962 though he had been separated from the PCA informally by 1959. By the early ’60s, the project of a communist psychiatry in Argentina had vanished—a full decade after it did so in France.

Meanwhile, in 1955, the country’s first psychology degree program had been established at what is now the University of Rosario and, in 1957, at the country’s largest institution of higher education, the University of Buenos Aires (UBA). Bleger held Argentina’s first chair in psychoanalysis in Rosario in 1959 and became the star of the UBA psychology faculty. In both institutions, psychology was first located inside the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, its students mingling with other humanities disciplines like history and recently established majors in anthropology and sociology, intensifying their sense of psychoanalysis as a social, theoretical discipline. Yet the new group of psychologists were professionally stuck: the APA, at the time the field’s only professional organization, rarely accepted members without medical degrees, nor, after the introduction of a state regulation in 1954, did the law allow them to practice psychotherapy. Private study groups proliferated, and APA members taught (and charged) psychologists, but were unwilling to grant them equal status; psychologists practiced informally, but the degree at UBA did not prepare them for clinical practice. Many were confined to mostly unpaid assistant roles at the psychiatry services that were quickly developing at various public hospitals around the country.

*

In the late 1950s, conservative asylum psychiatrists had total control over residency training for the discipline, and a struggle was underway to change the system. Reformist psychiatrist Mauricio Goldenberg was given control over the Psychopathology Service at a state hospital in the working-class Buenos Aires suburb of Lanús. He had a close, even brotherly relationship to Pichon-Rivière and described himself in an interview as integrating biological, psychoanalytic, and social points of view. He staffed the new service, which benefitted from its marginality and the inattention of the authorities, with young, untrained psychiatrists who worked without pay in exchange for training. Unlike traditional asylums, which were carceral institutions meant to contain the ill and avoid social degeneration, Goldenberg’s Lanús service emphasized collaboration with other medical specialties, free and open clinical attention for the community, and, for those who were admitted, a focus on healing and returning to life outside the institution. Goldenberg partnered with the APA, which provided him with “supervisors, teachers, and even a therapeutic staff group,” in exchange for training an “enormous quantity” of professionals, in the words of Enrique Carpintero and Alejandro Vainer in their two-volume, thousand-page Las huellas de la memoria [Traces of history]. Goldenberg also began to develop techniques for group therapy, a modality that has become defining of Argentine psychoanalysis.

As Carpintero and Vainer make clear, Goldenberg’s commitment to public relations is part of what made the Lanús service mythical and massively influential. He wrote and spoke often of the clinic’s work. His lieutenants gained renown as writers and leaders, and the service soon had a graduate degree and one of the first psychiatry residencies in the country. By 1967, he was made the first Head of Mental Health for the city of Buenos Aires, and each of its 25 public hospitals had a service modeled on Lanús, with a social psychological focus that synthesized psychoanalysis with psychiatry. Meanwhile, interest in psychology as a university degree was exploding, and the mental health field as a whole was becoming increasingly organized: the Federation of Argentine Psychiatrists (FAP) was founded in 1959 and the Buenos Aires Association of Psychologists (APBA) in 1962. The Graduate Psychotherapy School (now the AEAPG) was started around 1963 by psychology students and, much like the APBA, meant to organize the first classes of psychologists, whose professional ambit was heavily constrained by the APA’s chokehold on psychotherapeutic treatment. The school produced heavy tensions at the APA because eminent members (Ángel Garma and Arnaldo Rascovsky) had started the school from a private study group, the kind that analysts offered psychologists who couldn’t practice. The school was, as Carpintero and Vainer put it, “a way to institutionalize psychoanalytic training outside of the APA.”

“Mental health work continued to be organized around the public hospital services, which functioned horizontally and anti-hierarchically, a striking contrast to the highly verticalist, authoritarian regime that General Onganía had installed post-’66.”

The new class of psychologists—disproportionately committed to social work but without the cushy income of the analysts, who could subsidize their unpaid labor with a few weekly hours of clinical practice—grew increasingly radical as the ’60s advanced. A 1966 coup led to the “Night of the Long Batons,” in which university protests were broken up by police, violating university independence. The dictatorship closed the faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the University of Buenos Aires, forcing most of its professors into exile or unemployment, among them Bleger. The regime also banned political parties and set out to erode the power of unions. Mental health work continued to be organized around the public hospital services, which functioned horizontally and anti-hierarchically, a striking contrast to the highly verticalist, authoritarian regime that General Onganía had installed post-’66. Goldenberg and others in the leadership maintained good relationships with the regime: “Mental health reformers. . .deliberately steered clear of divisive party politics at the national level to maintain the paradoxical relationship that had developed between liberating psychiatric reform and Onganía’s repressive government,” Ramos argues.

In May of 1969, the Cordobazo, a brutally repressed mass protest in line with the global wave of unrest unleashed in May of 1968 and which kicked off the regime’s eventual downfall, led to widespread, public condemnation from the country’s mental health institutions. In Carpintero and Vainer’s words, it “marked a before and after in Mental Health.” The APA, which was historically and would mostly remain thereafter studiously apolitical, called for its members to strike in solidarity. In the heat of militancy, the notion of “Mental Health Workers,” stripped of the petit bourgeois appellation of “professionals,” took shape as a way to stand in solidarity with striking workers and which, Carpintero and Vainer say, “allowed [Mental Health Workers] to think of their contributions to social and political change.” They also received support from the FAP, which was going through its own leftwards transformation. Mental health workers traveled to the center of the demonstrations both as protestors and, much like Bermann in Spain, to assist protestors through their expertise. Unlike the APA-approved, hypereducated analyst, a bourgeois isolated from the world in the clinic, the mental health worker set out to remake society, not just ameliorate the ailments of individuals who could afford treatment. The three major mental health institutions were, soon thereafter, transformed: the FAP, for instance, elected José Bleger and other known leftist reformists to its leadership and stated explicitly its opposition to the dictatorship.

*

Argentina’s political climate continued to grow increasingly violent and polarized, with several leftist organizations—mostly petit bourgeois in composition—reorienting towards armed struggle. With a return to democracy in 1973 that led to Perón’s return from exile and into the presidency, conflicts between left- and right-wing elements of a Peronist movement that had largely been illegal since 1955, intensified. The studied neutrality of the mental health leadership became a problem for many, at first due to the willingness of Goldenberg and other leaders to receive funding from American (i.e., imperial) sources, including the Ford Foundation. The media theorist Oscar Masotta had begun, around 1965, to translate and popularize Lacan’s writing, which was received enthusiastically and challenged the APA’s strong devotion to the work of Melanie Klein. Psychoanalytic congresses both regional and international began to zero in on violence as a particular concern, with the approaches of more socially committed analysts being derided by the APA (and welcomed by the FAP). Two groups of analysts—later known as the Documento and Plataforma clusters—would begin to split away, first remaining in the APA but critical of the organization’s unwillingness to take sides. Ultimately, both groups met and coordinated their resignation from the APA, which overnight lost around 10% of its membership. Notably, Bleger—the father of leftist psychoanalysis—did not leave the APA, insisting that the institution required reformulation from within.

Marie Langer coordinated two volumes titled Cuestionamos [We Question] and later Cuestionamos 2 in which affiliates of Plataforma and Documento made clear their distaste for the APA. As the Plataforma statement read: “For us, from now on, Psychoanalysis is not the official Psychoanalytic Institution. Psychoanalysis is where psychoanalysts are, understanding being as a clear definition that does not pass through the field of an isolated and isolating Science, but through a science that is committed to the multiple realities that it aims to study and transform.” Most in the APA remained unmoved, but the splinter made waves globally: it was the first such break with an affiliate in the IPA’s history. Meanwhile, the FAP membership came under fire, with multiple prominent psychiatrists fired from their positions.

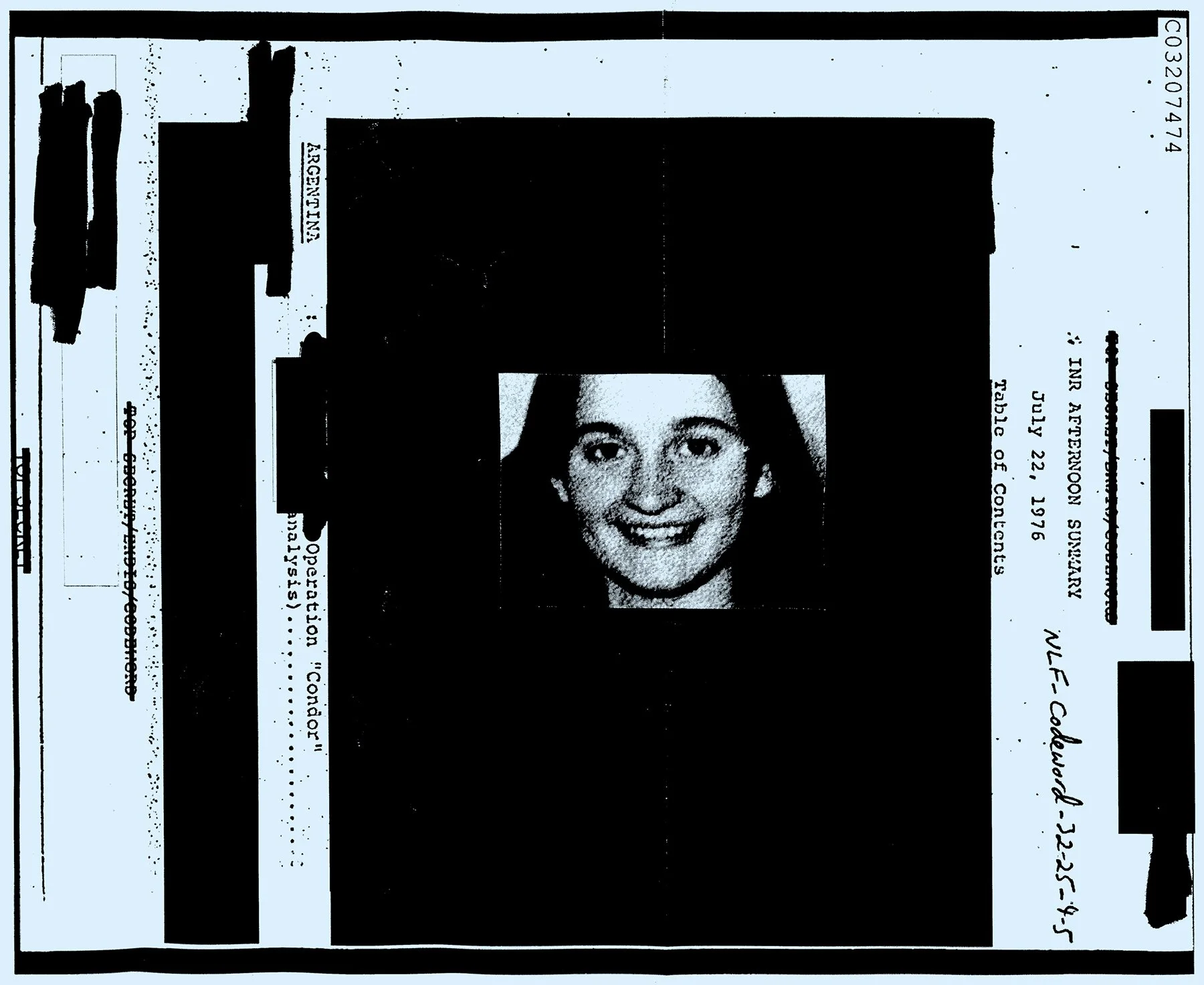

What was once a small, marginal movement had grown and splintered, fractured by the internal contradictions of its members’ political orientations. Few, if any, were in any way connected to the armed struggle guerrillas whose activities intensified leading up to the March 24th, 1976 coup. Bleger died in 1972 while Langer and others fled into exile in 1974 or 1975 after being threatened by the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (Triple A), a state-sponsored paramilitary organization that developed the system of disappearances later used by the dictatorship to execute around 1,000 purported communists and threaten many more. When the dictatorship arrived, even more mental health workers fled into exile, while many more forsook participation in the various organizations. Goldenberg ran to Venezuela. The Lanús service, which had been the centerpiece of his life and of the reformist, community-focused movement, was shut down, as were others, allegedly staffed by subversives. Multiple psychiatric hospitals were, furthermore, made into clandestine detention centers, effectively concentration camps where the disappeared could be held, tortured, and likely executed. Of the 400 disappeared, Beatriz Perosio, then the head of the APBA, was the most notable. Other practitioners, like Hugo Vezzetti, who succeeded Perosio at the APBA, were interviewed by Argentina’s intelligence services to ascertain their ideological background.

“Multiple psychiatric hospitals were, furthermore, made into clandestine detention centers, effectively concentration camps where the disappeared could be held, tortured, and likely executed.”

Yet, Ramos argues, while the regime as a whole publicly disdained communitarian approaches and made advances to reinstate asylum-based, biological practices, it also adopted some of those practices. Put simply: “[t]he government cared less about the details of psychiatric practice and theory than the political orientation of mental health professionals in the country. Once the political statement that the government would not tolerate leftist psychiatrists had been made, psychiatric practice proceeded relatively unperturbed.” Right-wing magazines would go on to situate Freud as a defender of traditional family values, acknowledging the depth of psychoanalysis’ involvement with Argentine society while reconfiguring its valence. It was, in Ramos’ terms, a “welcome addition to the government’s ideological arsenal,” a useful complement to their wider project of societal transformation and atomization.

Of the many reformist mental health organizations, only the FAP survived the dictatorship, though it lost multiple members to the dictatorship’s genocidal program and much of its public exposure evaporated before it disbanded. Mental health was never the same. Marie Langer died in 1987, returning to Buenos Aires after a decade of exile in Mexico; Goldenberg in Washington, D.C. in the 2000s. The dictatorship succeeded in atomizing psychoanalysis, solidifying its ameliorative and individual elements to the detriment of its practitioners’ commitment to community action. In fact, the dictatorship largely succeeded in exterminating the left in Argentina: we still live in the wreckage it created and the absences left behind.

The psychoanalytic culture that emerged from the dictatorship, which ended in 1983, has not yet been studied in depth. The clinic has been televised and governed by apolitical self-helpish hacks like Gabriel Rolón, who frames his psychoanalytic thought in line with prosperity gospel and a banal individualism. Fascism or its degraded copies are rising, and with them the question of the community clinic—not the exception but the rule, a bulwark or a barricade—is unavoidable. For now, in an Argentina governed by a president known privately and publicly as “The Madman,” the private clinic replaces the service as the horizon of analytic labor. The community vanished, destroyed together with so much of our once-organized community, and never quite returned.