On Helplessness

When All That’s Left Is to Refuse to Be Saved

nadia bou ali

In the most complex moments of reflection on war and death, aggressivity and narcissism, Freud often resorted to the crucial concept of Hilflosigkeit, helplessness, to understand the cruelest acts of humanity. Helplessness is the drive against which humanity seeks to assert itself: the becoming human of the subject against the regressive drive for dependence. We seek dependence because we want to ensure that the object we love will not become the very object we hate; we seek permanence in love because we harbor the fear of love being taken away. Love is the guarantee for our existence in so many ways: it offers a relation, a refuge, a place for which there is none. It binds us to a group, a master, a signifier that then promises a guarantee for the original loss that was our original helplessness—an amoeba-like emotion that scours the world in search of an extension, a libido in the place of spirit.

Freud suggested that this primary helplessness explains our most intense feelings of love and hate and our most intense feeling of lack. A primary mover of non-Aristotelian nature, it is not a potentiality in search of actualization, but rather a burdensome negative that signs off at every encounter, in every relation. This helplessness is in one sense ontological, but not only. It also inflects our ways of knowing, of enjoying, of making sense of the world. This is further elaborated by Lacan, for whom Hilflosigkeitis the springboard of sense. It propels the latching onto a primary signifier, language, meaning-making, the symbolic. It explains our entrapment in chains of signifiers, the enchainment in the guarantee of language. In many ways, this originary helplessness is the catalyst of attachment, and the very sense of an end in analysis. Subjective destitution at the end of analysis invokes yet again this sense of helplessness, of detachment, of a lack of guarantee. We thus begin right where we ended: the means-and-ends problem is resolved, albeit momentarily.

Freud’s most incisive comments about Hilflosigkeit followed in the wake of World War I and make a strong appearance in his analysis of group formations. He maintained that we identify with the group precisely because we are so helpless in our ego. The ego strives to be omnipotent, to be great, again and again, yet fails. It needs a sense of an outside that will give it a boundary and threaten its limits at the same time. The ego is a master negotiator, always seeking the best deal, hedging against its losses, speculating on its eternal future, for it cannot be otherwise. When the ego cannot avow its helplessness, it disavows it, weaving tales and stories, imagining psychic reality anew. This reliance on the help of others, the charity in social relations, is the ego’s fantasy. What psychoanalysis promises is that the subject will be able to survive witnessing its own helplessness. This is not a group affair, though often groups canalize this primary originary emotion.

“What psychoanalysis promises is that the subject will be able to survive witnessing its own helplessness.”

Frantz Fanon maintained that this obfuscation of helplessness is made clear in colonial contexts when the group or family abducts the libido: magic, myth, ghosts from the past haunt the colonized excessively. The enemy within, so to speak, is one that haunts the colonized in a “permanent confrontation on the phantasmatic plane,” where there is a “disintegrati[on] of personality, this splitting and dissolution.” This dissolu-tion of personality, this libidinal cooptation by the group, is precisely what the native, the colonized, sheds during the battle for freedom. The “centuries of unreality” are pushed back into the past as the native fights back against real demons of colonization. Fanon’s claim is that the “exit from the imaginary” compelled by colonization is a moment of violent confrontation: there can be no compromise except for the national bourgeoisie, the elite who will negotiate with the colonizer and run things on their behalf. Those natives or colonized who do not fight are beaten from the start, retreating into their helplessness as the “bombs [are] raining down on them.” This helplessness in the face of colonial power implies that one is already beaten, that whatever they do, they have already lost. Helplessness in this context comes to signify that they are yet again a mass, a population, a group. The only way to conquer this helplessness, to not give into it, is to fight. Though they know very well that only the violence of the colonizer will be justified, and not that of the colonized, they know also that it is only “this apparent folly alone that can put them out of reach of colonial oppression.”

Fanon accurately observes that the politics of anticolonial liberation is always stuck between being too quick (too much fighting that leads to burnout) and prematurely giving up. His comments come in the context of the Cold War, when he thought that “capitalism realizes its military strategy has everything to lose by the outbreak of nationalist wars.” During this time, colonies had to disappear for capital’s development: “what must at all costs be avoided is strategic insecurity.” The binary Cold War system fed violence into the colonies—while the two blocs had cold coexistence, the colonies boiled. Fanon predicted that a politics of minorities (the Negro, Muslim, and Jew) would follow, entailing the “use [of] the people against the people.”This has become the legacy of postcoloniality.

The Cold War world was, of course, another world, another time, another stage of capital when neutralism dominated the Third World and aid flowed in from both sides. The governing classes of the Third World, Fanon wrote, were “men at the head of empty countries, who talk too loud, are most irritating. You’d like them to shut up. But, on the contrary, they are in great demand.” Meanwhile, the persistent outbreak of violence in the Third World, the Global South, is itself a result of the Manichean world of colonization: “[i]t’s them or us” is the lesson that the colonizer teaches. Force is the only way forward that brings together the colonized in the sole aim of taking out the settler, of getting rid of them, of uniting to kill them: “To work means to work for the death of the settler.” The path of armed struggle is one of no return, writes Fanon: “terror, counterterror, violence, counterviolence.” The story Fanon tells is not so out of date: colonialism unifies the colonized through a violence that both reinforces their unity and threatens it with separation. The inter-national order itself is built around this structural violence. Any real move toward independence is threatened by the economic withdrawal of the West: “[t]he apotheosis of independence is transformed into the curse of independence.” Fanon understood well that the only way to overcome colonial violence would be through a global redistribution of wealth. We are now in the thralls of a neocolonial violence of different proportions: the rise of mercantilism and the reemergence of fascism are propelled by a logic of redistribution of wealth between nations, blocs, and empires, but not within them.

For instance, the excuse of wealth redistribution to benefit the American working class is a farce: the colony has come home, the new cycle for the Western lower and middle classes is recession, depression, rebellion, civil war—lest we forget, Nazism transformed all of Europe into a colony. While Germany did pay in retribution, Europe never paid its dues to the colonies. America never paid, either, and is now seeking further extraction.

It is crucial here to quote the full picture Fanon paints:

As soon as the capitalists know—and of course they are the first to know—that their government is getting ready to decolonize, they hasten to withdraw all their capital from the colony in question. The spectacular flight of capital is one of the most constant phenomena of decolonization.

Private companies, when asked to invest in independent countries, lay down conditions which are shown in practice to be inacceptable or unrealizable. Faithful to the principle of immediate returns which is theirs as soon as they go “overseas,” the capitalists are very chary concerning all long-term investments. They are unamenable and often openly hostile to the prospective programs of planning laid down by the young teams which form the new government. At a pinch they willingly agree to lend money to the young states, but only on condition that this money is used to buy manufactured products and machines: in other words, that it serves to keep the factories in the mother country going.

In fact the cautiousness of the Western financial groups may be explained by their fear of taking any risk. They also demand political stability and a calm social climate which are impossible to obtain when account is taken of the appalling state of the population as a whole immediately after independence. Therefore, vainly looking for some guarantee which the former colony cannot give, they insist on garrisons being maintained or the inclusion of the young state in military or economic pacts. The private companies put pressure on their own governments to at least set up military bases in these countries for the purpose of assuring the protection of their interests. In the last resort these companies ask their government to guarantee the investments which they decide to make in such-and-such an underdeveloped region.

It happens that few countries fulfill the conditions demanded by the trusts and monopolies. Thus capital, failing to find a safe outlet, remains blocked in Europe, and is frozen. It is all the more frozen because the capitalists refuse to invest in their own countries. The returns in this case are in fact negligible and treasury control is the despair of even the boldest spirits.

In the long run the situation is catastrophic. Capital no longer circulates, or else its circulation is considerably diminished. In spite of the huge sums swallowed up by military budgets, international capitalism is in desperate straits.

The abandoned Third World, condemned to regression, is now stuck in a “collective autarky.” Fanon continues:

Thus the Western industries will quickly be deprived of their overseas markets. The machines will pile up their products in the warehouses and a merciless struggle will ensue on the European market between the trusts and the financial groups. The closing of factories, the paying off of workers and unemployment will force the European working class to engage in an open struggle against the capitalist regime. Then the monopolies will realize that their true interests lie in giving aid to the underdeveloped countries—unstinted aid with not too many conditions.

Aid is today precisely what is being blocked and we see more monopoly, more hoarding of wealth, more avarice. All the gains of decolonization are being lost.

It cannot be overstated how closely Fanon’s imagined conditions resemble the conditions of the Western working class today: colonization has come home, full circle. Yet we are far from the unification of the European or American working class. Instead, we are witnessing the rise of fascism yet again, under a liberal consensus.[1] Helplessness, depression, dependency, fear of loss of love, anxiety, fascist populism swirl into the disastrous cocktail of our political present.

The helplessness of the colonized is converted into the helplessness of capital. Capital can’t help itself; it must be helped, it must be kept in its original version, industrial capital, not the suicidal drive of speculation and markets. While the first Cold War was a bad idea for the colonized, a tragic end to anticolonial struggle, as Fanon tirelessly repeated, the fabricated and farcical cold war being staged today is even worse. The tariff wars have overshadowed colonial genocide. Elon Musk losing over $100 billion makes the headlines, while the headless children accumulating in Gaza’s morgues do not. This is not a sentimental comment: it indexes what we could call the law of conversion of helplessness into dependency. There is a courage in Fanon’s obstinacy when he states there is no use repeating “that hunger with dignity is preferable to bread eaten in slavery.” Decolonization implies making sure the colonized don’t starve, that the material conditions for the survival of the colonized are furnished so that they may not forget their dignity. Dignity is gained through political reform, and only with dignity can the colonized fight colonization. It is this dignity that colonialism works to dismantle. Fanon’s analogy is striking: colonization is not comparable to a protective mother who seeks to guide the colonized from darkness to light, but a mother who “unceasingly restrains her fundamentally perverse offspring from managing to commit suicide and from giving free rein to its evil instincts. The colonial mother protects her child from itself, from its ego, and from its physiology, its biology, and its own unhappiness which is its very essence.”

The colonial mother protects the colonized from their own version of helplessness, their being-unto-death. It is the colonial mother, then, that teaches children not to turn themselves into human shields, not to self-destruct, not to self-incarcerate. They want to be in a prison, in an enclosure, they do not wish to leave, they wish to be governed, they are so helpless that they know not what to do with themselves. We offer them free trade, rivieras, havens of commerce; they want anachronistic things like a nationality and a name. How bizarre is their helplessness? How does it conceal our own disavowed helplessness?

“[T]he colonized have another take on helplessness, an obstinate strength in living in it, in knowing that no one will come for them, no one will save them.”

Yet the colonized have another take on helplessness, an obstinate strength in living in it, in knowing that no one will come for them, no one will save them. There is nothing to be done except to hold their ground, to refuse to be saved, despite wanting to be saved. Who does not want to be saved? Who does not want to save the helpless? These questions call forth another world as answer, a world in which helplessness is not a source of the production of systemic enjoyment.

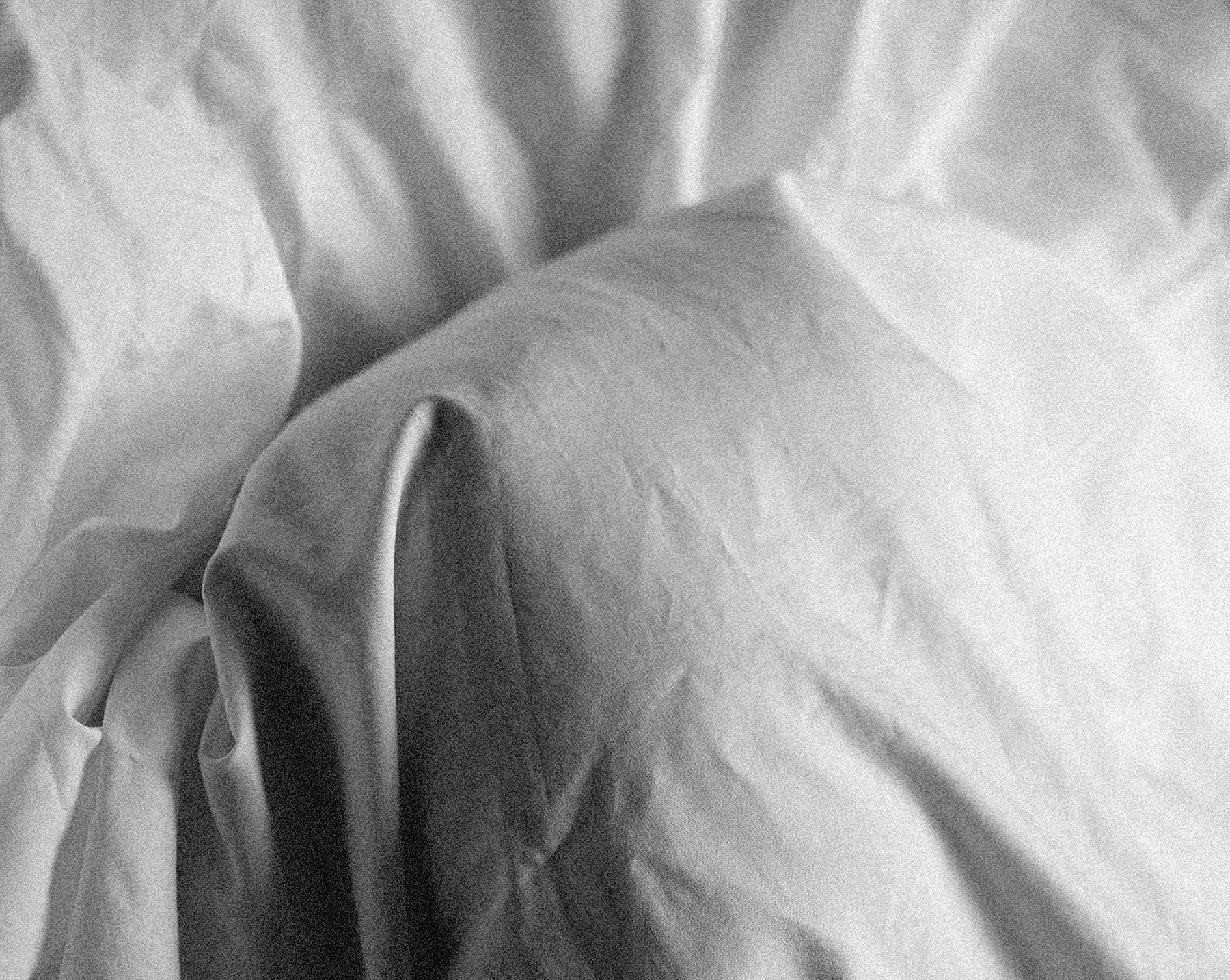

There is a deep cruelty in psychoanalysis that does not sit well with Marxist politics. It is the cruelty of asserting that there is no escape from ambivalence: life and death, Erosand Thanatos, love and hate, desire and demand, helplessness and the demand for recognition. Nowhere is this problem more evident than in the colonial context. However, unlike Romanticism, and unlike Hegelianism, this eternal duel, this struggle unto eternity (of life and death, of the drives) is for psychoanalysis rooted in the body. It is the body on which the drama of helplessness, of ambivalence, of repression and of the return of the repressed plays out. In con-trast to the phenomenological suffering of the body, the eternity of the unconscious, in its timeless struggle, betrays that in fact there is no time. Time can be abolished. However, the lesson of psychoanalysis is that there is a way into the unreachable noumenal reality of Kant: time-consciousness is a rationalist disease, a disease of repression. There is no other time but this time.

The anticolonial struggle in Palestine is an opening of this problem of eternity: there is no delay, no postponement. The colonizer knows that, wishes to shut the gates of time, rushes to exterminate the bodies that are aching with the timelessness of their struggle, in the eternal labor of becoming subjects, in the “Sabbath of Eternity.”

This is perhaps the most radical proposition of a speculative theory of helplessness and ambivalence: there is a heroism in witnessing the dissolution of the fantasy of omnipotence generated by the disavowal of our impotence.

Anticolonial struggles offer us a fundamental scene for traversing such fantasy. Not only is the impotence of the colonized avowed (a great lesson of Fanon’s account of doubled alienation), but it is also never realized. The fight against colonialism, against the violence of occupation and erasure, is a fight against the irrealization of impotence. Helplessness cannot be helpless; suffering is not a pathos—it is interrupted, unrealized. Suffering does meet recognition, or a symbolic guarantee to hold it together. In this way, the drama of helplessness is withheld from developing into the dialectic of recognition and misrecognition. It does not translate, it is withheld from dependency by the image of its pathos. Suffering is not sublated into anything but bodies that can be counted in an infinite tally. For the colonizer, there is no body count because the bodies do not signify. This wager is hard to stomach for any liberal still entertaining fantasies of progress, still banking on democratic representation, on the public sphere, on theories of justification, on plural forms of knowledge and relativist epistemologies: this is really, truly the end time, or the time of the end.

The game is over: the only thing that will live on is the dead, precisely because we can never imagine their deaths. We can create apparatuses, algorithms, calculations for why their deaths make sense, but we cannot enter their count. They are helpless unto death. Not beings-toward-death that flag a fantasy of authenticity, but bodies that signal a helplessness that cannot be overcome, that stage it, heroically embrace it: the old die with the young, the young watch the old die, the old know that the young will die. No one is rushing to the borders of the desert seeking refuge. There is no messiah, no one to come to lead them anywhere; there is only the collapse of civilization.

The rationalists who hope for a moment of reason, when all this suffering will tally up, make sense, deliver us to the absolute, only for it to revert to its older forms . . . none of this works, it doesn’t work anymore. We are at a real day of reckoning: the helplessness that we all work so hard to disavow is threatened by extinction, whereas the dialectic of enlightenment saw that extinction would be precisely what propelled reason forward. The way forward from the detritus of human remains accumulating in Gaza appears to be a return to the barbarism of our modern civilization, which is based on the deadening of life in the drive toward accumulation.

[1] For further discussion see Zahi Zalloua, “Fascism from the Standpoint of Its Racialized Victims,” The Philosophical Salon, March 24, 2025. thephilosophicalsalon.com/fascism-from-the-standpoint-of-its-racialized-victims/; Alberto Toscano, Late Fascism: Race, Capitalism, and the Politics of Crisis (Verso, 2023).